Organized Resistance

A note on framing

We are deeply sensitive to the historical and essentializing modes of portrayal of Indigenous stories in archival research. Historically, Indigenous folks have been positioned as the studied, rather than the studiers, and a particular Euro-centric framing has emerged in academic literature. As such, we have leaned heavily on the Prairie Island Nuclear Coalition newsletter for an accurate depiction of Indigenous reactions and solidarity.

Prairie Island Coalition

Formed in 1990 by about thirty member organizations, the PIC was organized to oppose Northern States Power’s plans to expand its storage of nuclear waste in Minnesota.

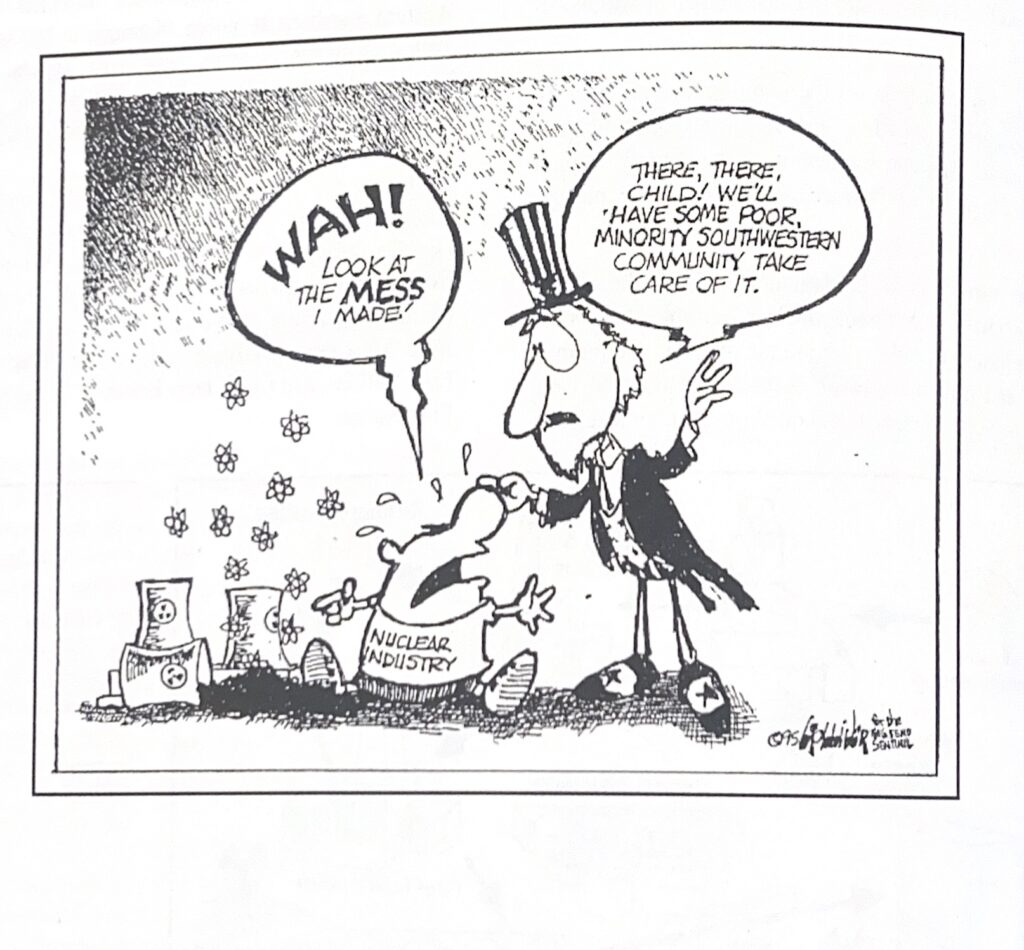

Nuclear Racism: The operation, siting, or the attempt to site a nuclear facility within or near a community of color; to choose a community of color over communities that are primarily affluent and white.*

*listed alongside definitions of nuclear classism and nuclear colonialism

Page 4

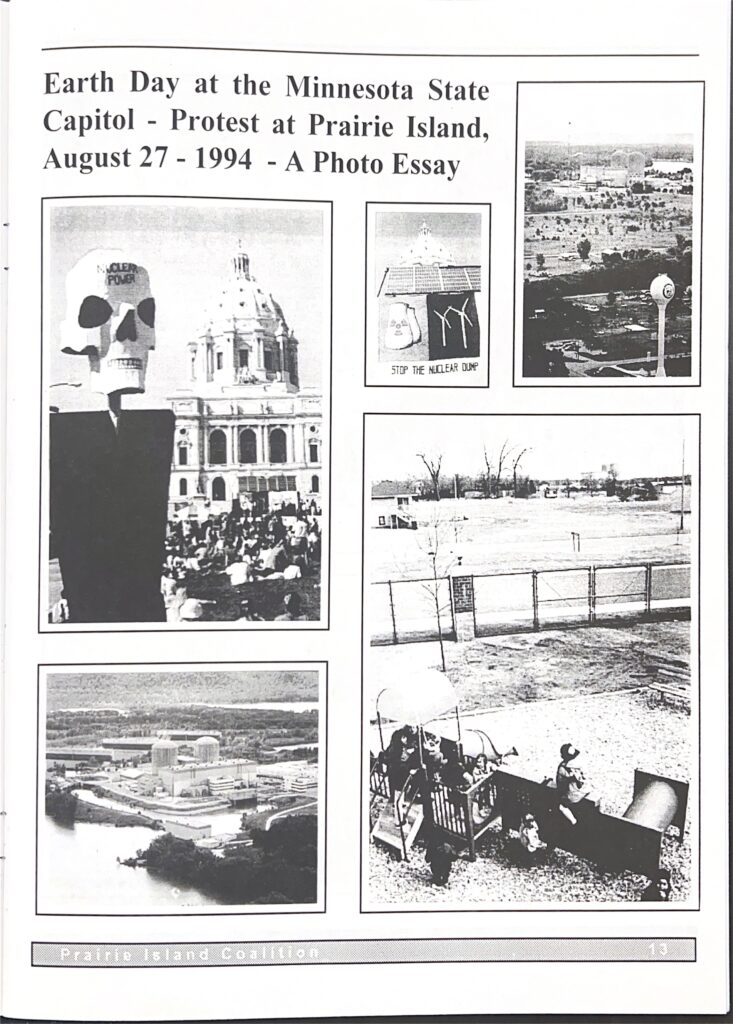

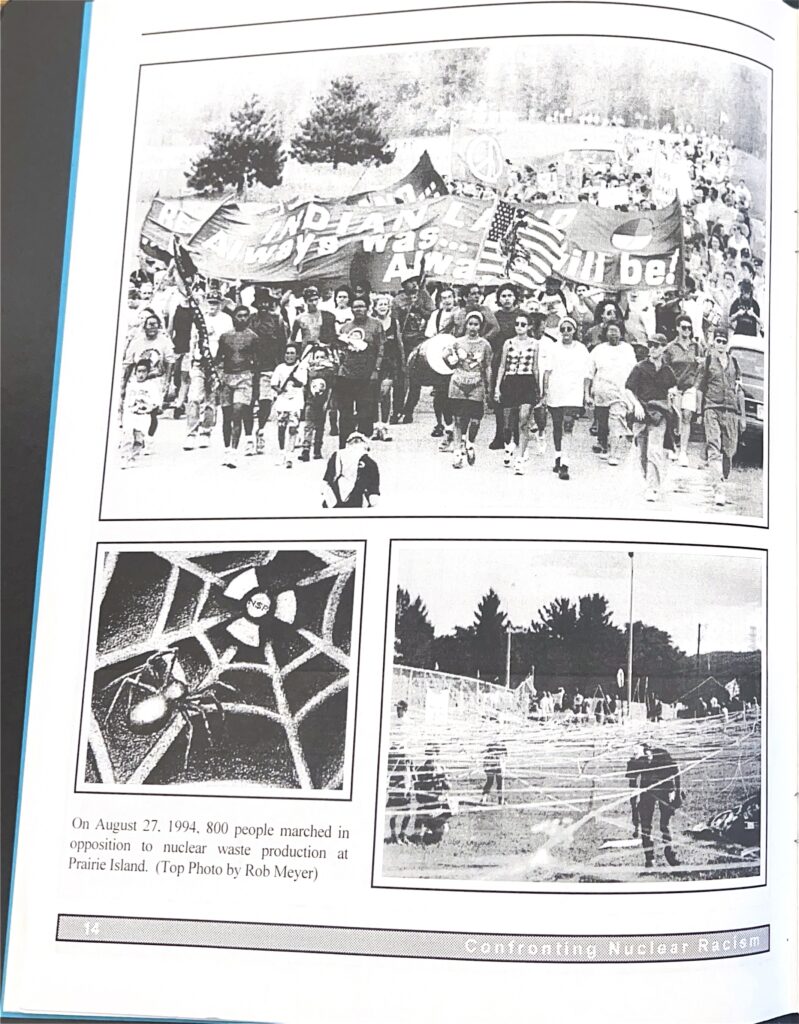

Some 30 years ago, on Earth Day, over 800 people marched on the state capitol to protect nuclear waste production at Prairie Island. NSP had already been storing waste there for decades, but a series of recent floods and PIC organizing have alerted people to the danger. After pushing hard in the state legislature, NSP wins 17 more casks to store at Prairie Island. They will not be stored at Monticello, which is located up-river of the Twin Cities, and thus politically unviable.

The 1996 report demonstrates a high level of solidarity in the PIC among indigenous groups across the country. The stories of 7 communities affected by NSP’s nuclear chain are included: the Pueblo of Laguna (NV); Homer, Louisiana; Prairie Island; Western Shoshone (NV); Mescalero (NV); Meadow Lake First Nations (SK) Sagkeeng First Nations (MB) . The PIC embodies the connection that Abena Dove Osseo-Asare identifies in Atomic Junction: all of the people whose lands have been seized for nuclear activities are linked by a common experience of living on atomic lands.

They are participants in a nuclearized frontier zone where local populations lose access to territory through new regulations and secret scientific activities

Abena Dove Osseo-Asare 2019, 142

| NSP Nuclear Activities as Described by PIC Report 1996 |

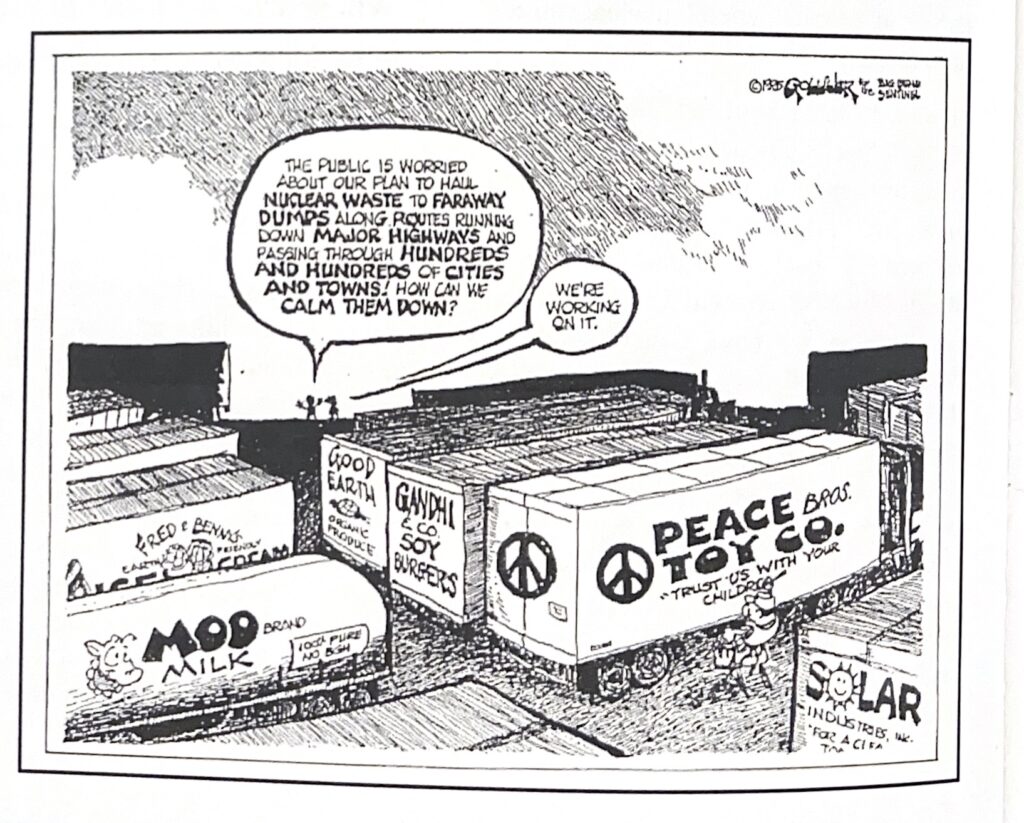

It’s important to understand that a key priority of the PIC is to keep reminding the public that support for the storage of nuclear waste is not high, and it’s not increasing. NSP, Xcel, and other corporations rely on the tacit approval of citizens who are not exactly comfortable with what they are doing, but believe that enough other people are that their voice does not matter. This is a classic move in the playbook of neoliberalism in general, and settler-colonial actors in particular.

There is clearly a pattern here in NSP and other nuclear powers strong-arming their dangerous activities onto Indigenous lands. In these examples and others, more affluent and politically-influential communities rejected hosting nuclear activity because of the risks to public health.

In the end, it was difficult to find information about why exactly NSP built a nuclear plant near Prairie Island.

Nick Martin, representative from Xcel Energy, had this to say:

“So I would say the initial siting decision was a combination of that original land sale from the Army Corps of Engineers – for a coal plant, with good river and rail access — and later the rapid growth of the Twin Cities and need for a large power source to balance the electrical system to the southeast.”

All information accessible in the archives of the Gale Family Library located at the Minnesota Historical Society.