“IF ONE is to judge from the infrequent notice given the Prairie Island colony in the

Meyer 1961

local newspapers, the attitude of the surrounding white community was not altogether sympathetic. When these Indians are mentioned at all, it is in tones of condescension and tolerant amusement, and

attention tends to be focused on the occasional cases of drunkenness, petty thievery,

and quarreling within the band. “

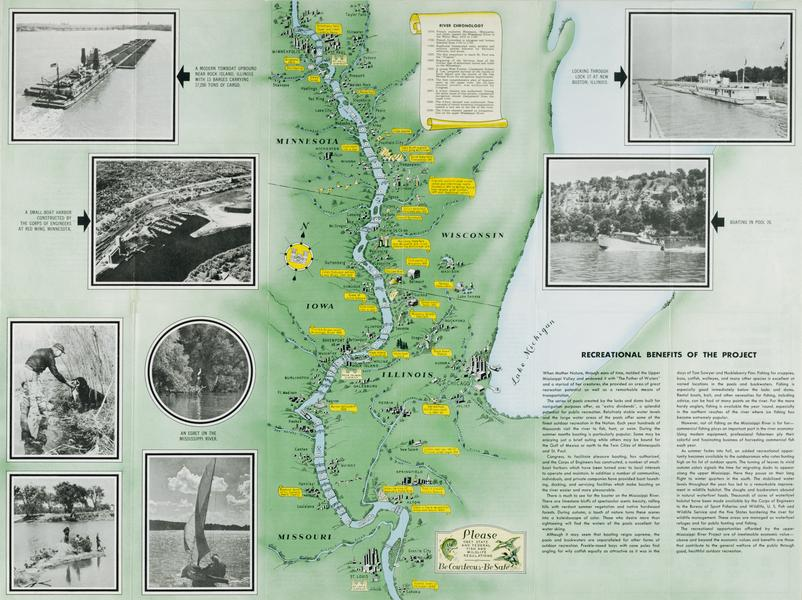

Located on the banks of the Mississippi River the Mdewakanton, “those who were born of the waters, were officially recognized as the Prairie Island Indian Community in 1936. The initial reservation of 534 acres secured the sacred grounds for the community to grow. Just as the PIIC began to find stable footing on their homeland, two years later the Army Corps of Engineers would construct Lock and Dam no. 3 just south of the reservation cutting the reservation size down to 300 acres.

Amid the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration promised to build transformative infrastructure and employ American workers. Pitched as a transformative investment in the Upper Mississippi River, the nine-foot channel project built the locks and dams needed for commercial shipping projects. It also promised enhanced recreation, flood control, and to link river communities to each other and the world.

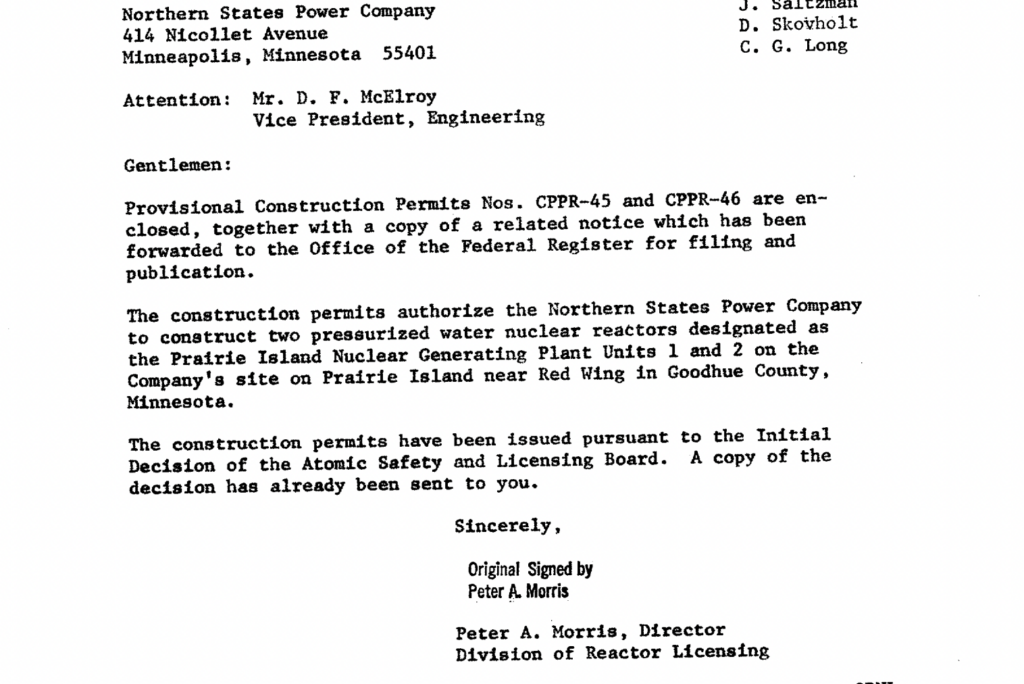

Located 28 miles southeast of Minneapolis, the Prairie Island Nuclear plant began construction in 1968 and achieved its first commercial operation in 1973 under the Northern States Power Company. The land was sold by the Army Corps to NSP in the 1940s for a coal-fired plant. Reports from the period indicate that the area was a low population zone, with the surrounding land being used for agricultural purposes. In the late 1967 Dr. Elden Johnson, the Minnesota State Archeologist, surveyed the land, excavating burial mounds. However, reports are critical of his work stating he did not focus on the site of the power plant.

Decades of policy choices and projects on the upper Mississippi have failed to consider the Prairie Island Indian Community. Infrastructure projects have chosen outside communities as the beneficiaries at their expense.

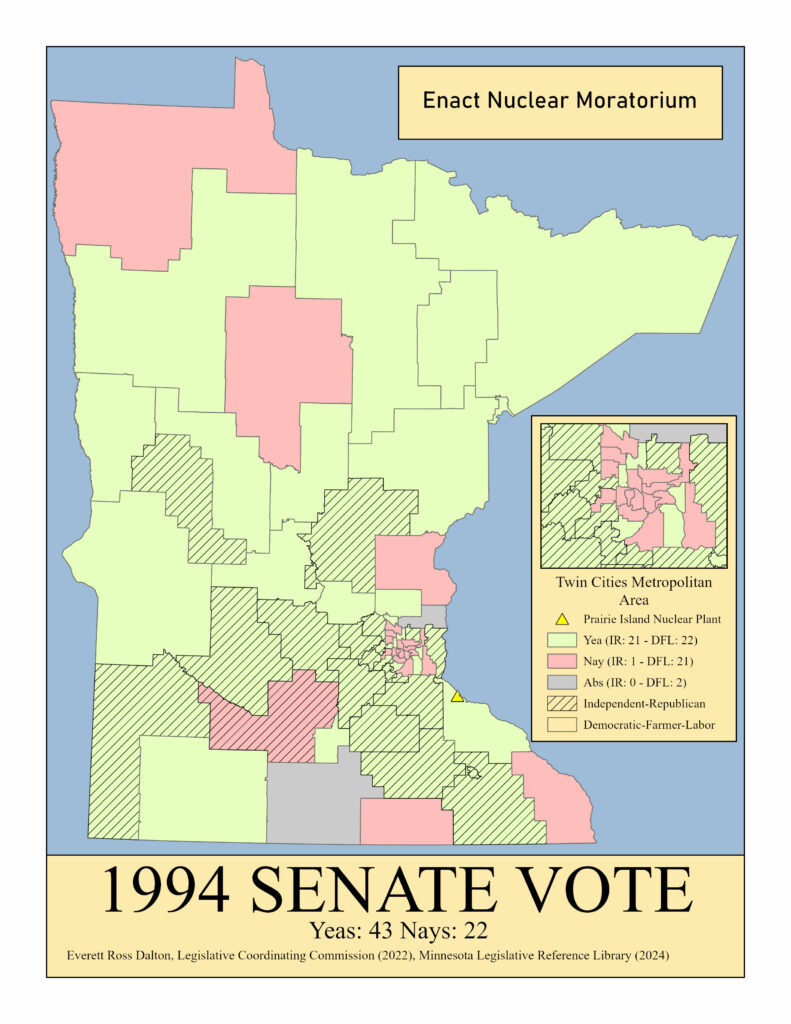

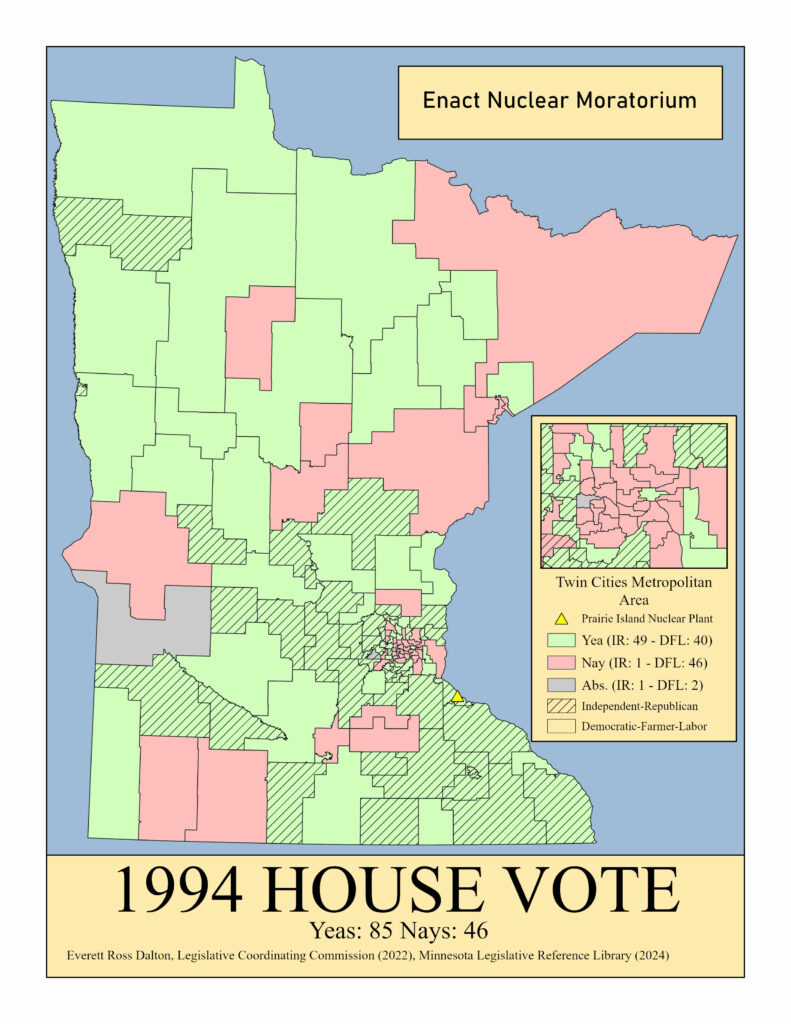

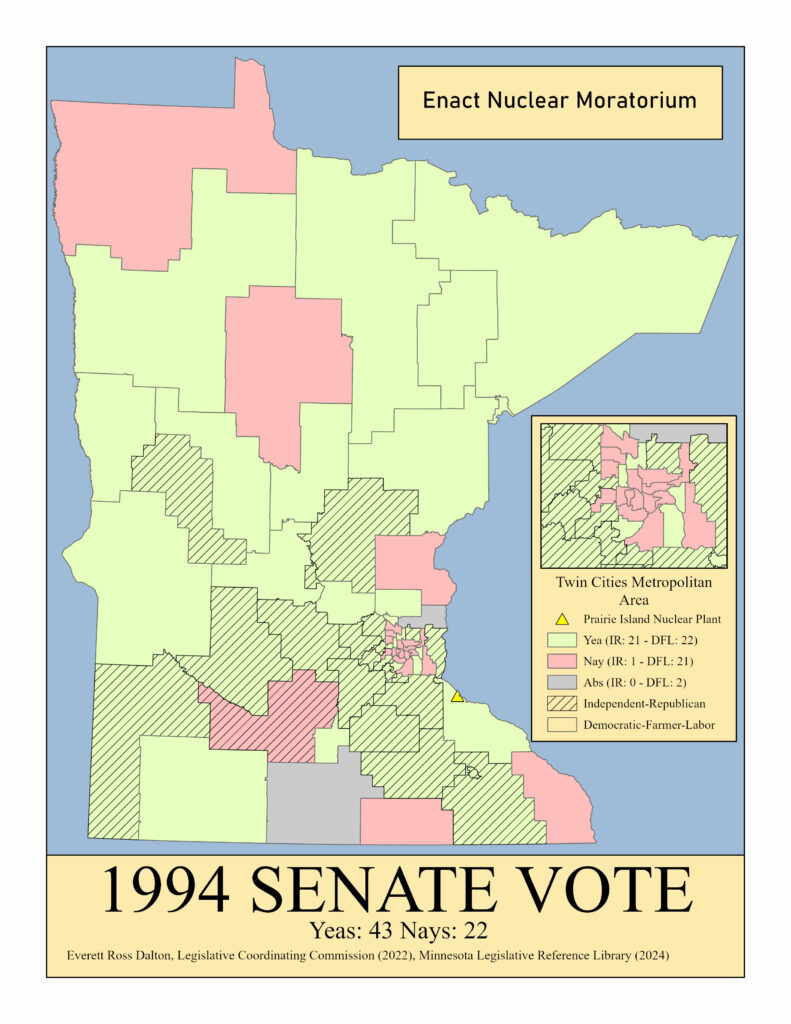

1994 Moratorium Passage Analysis

The vote in 1994 on the nuclear power moratorium is honestly quite mystifying at first glance. When I listened through the audio of the legislative debate surrounding the bill that contained the moratorium, I found nothing but discussion of nuclear waste storage policy. The moratorium only occasionally appears, is touched on, and then promptly ignored. Here’s what DFL senator Steven Novak (author of the bill) had to say about the moratorium as he introduced it:

The only other mention I can find comes briefly in the testimony of a representative of Northern States Power, the company that would become Xcel Energy and then-operators of the Prairie Island Nuclear Plant (PINP):1

And that’s it. In what I listened to of the committee meeting that audio came from, the moratorium itself never comes up again. Proponents of the bill seemingly never justify their want to move away from nuclear energy, and opponents of the bill never try to oppose it. Most confusingly, Prairie Island Indian Community (PIIC) members and their supporters seem to be arguing against the bill despite the moratorium being in it. What’s going on here?

We can start to unravel this once we understand that, had the state not intervened, the PINP would have closed soon after 1994. The PINP was struggling to deal with its high amounts of nuclear waste, and if they couldn’t find anywhere to store it, the plant would close.

The proponents of the bill wanted to prevent this from happening. Their argument was largely focused on sustaining the “high paying jobs” that the PINP provided and avoiding the negative effects that the plant’s closure would have on the local economy of the city of Red Wing (though not the PIIC). Here’s Senator Novak making that exact point:

Property Taxes:

Jobs:

This clip’s a bit longer, but gives more detail on the jobs perspective, if you have the time:

Or, making it even more clear, Senator Novak said this about opponents of the bill:

Proponents of the moratorium, then, were not trying to limit harm to indigenous communities. In fact, they explicitly opposed storing nuclear waste in any place other than next to the PIIC. This comment by Senator Andersen, an opponent of the bill, underlines this well:

Senator Morse’s point against just a bit later in the same session is also relevant here:

But still, this leaves the question: if they were so protective of nuclear development, why even include the moratorium in the first place?

The proponents give us no answer on this point, but the arguments made by the opposition might just give us a clue.

Opponents of the bill were fine with the plant shutting down and, frankly, seemed to welcome it. One person who testified against the bill in the Jobs, Energy, and Community Development Committee said:

Opponents feared that the waste storage would be permanent no matter what sorts of promises were made by proponents. And while I won’t comment too much on waste storage, this seemed to reflect back onto fears of the permanence of nuclear power at Prairie Island in general. Here’s the testimony of a member of the Prairie Island Tribal Council:

Moreover, they were afraid of nuclear disaster, and rightly so. One citizen testifying against the bill in the Jobs, Energy, and Community Development Committee noted his observations of the perilous state of PINP:

But more than that, opponents of the bill and moratorium were afraid of nuclear disaster in the wake of decades of previous nuclear disasters that weighed on their minds. It most obviously shows itself in one illuminating clip of a gallery member who suddenly shouting out something in response to a rehtorical question by Senator Novak:

Chernobyl had just happened eight years prior, in 1986,2 and it’s safe to say the fear it inspired of nuclear power was still fresh in the public’s minds. Not to mention the accidents that occurred in the United States. From the little-known SL-1 disaster in 1961 to Three-Mile Island in 1979 to a series of forced shutdowns across the United States from 1987-1989,3 each nuclear accident further fueled the rise of a strong anti-nuclear movement,4 and it began to bear fruit in other nuclear power bans across the United States.5 Just after Three-Mile Island, Oregon quickly passed a nuclear moratorium in response to public outcry,6 and even bans in Wisconsin in 19837 and Kentucky in 19848 could have been influenced by this.

It’s no wonder, then, that legislators and ordinary citizens alike continued pushing the proponents about what would happen if something went wrong with the waste storage. The Proponents’ only response was to slap them with the response, “Dry Cask Storage is safe, or at least safer than pool storage.”

Here is one clip from the Jobs, Energy, and Community Development hearing that, while long, sums the entire debate up well:

In face of this opposition, then, the moratorium could be seen as a method of convincing those moved by anti-nuclear activists to ignore the persistence of nuclear power by giving a half-measure. This moratorium offered proponents an option that effectively kept the status quo for energy generation and the energy economy while preventing nuclear power from spreading everywhere outside Monticello and Prairie Island. From a self-interested perspective, its easy to see why one from, say, the Twin Cities (upstream of PINP) might support this thinking they are doing good.

So, to sum up…

Why vote for the Moratorium in 1994? Because you want to avoid job losses jobs and keep the local economy steady without large disruptions, and you have to convince people with anti-nuclear sentiments influenced by strong anti-nuclear activism that you’re on their side. Because you are willing to put indigenous populations at further heightened risk of ecological catastrophe for the sake of broader economic growth.

Why vote against the Moratorium in 1994? Because it was a distraction from the necessity of tearing down the Nuclear power infrastructure that has had discriminatory impacts on the PIIC. Because one slip-up could make Prairie Island the next stop in a line of nuclear disasters that had occurred over the preceding decades, which would destroy the Prairie Island ecosystem for thousands of years.

Audio Sources:

Floor Session, Committee Session 1, Committe Session 2

Further Reading on Moratoriums

Post 2000 Nuclear Policy: The Burdens of Bureaucracy

Since the passage of the original 1994 moratorium on the construction of nuclear energy plants in Minnesota, there have been a number of legislative attempts to repeal the moratorium, as well as bills to increase nuclear waste storage capacity in Minnesota. These bills have reflected bipartisan efforts regarding the usage and regulation of nuclear power in Minnesota. Both political parties have played roles in promoting, regulating, and evaluating nuclear energy’s role within the state’s energy portfolio, indicating a dynamic and ongoing debate over nuclear power’s place in Minnesota’s energy future. So far, none of the bills seeking to repeal the moratorium have passed in the legislature, nor have any attempts to create “carve out” amendments that create exceptions for smaller reactors, as was introduced by Senator Andrew Mathews in 2023.

Photo of Prairie Island Nuclear Plant, Credit to Xcel Energy

Intensive Legislative Activities in 2003

In 2003, during the 83rd Legislature, two significant bills were introduced that would set the tone for Minnesota’s approach to nuclear energy and renewable initiatives. HF775 and SF794 sought substantial changes, including the redefinition of what constitutes a radioactive waste management facility. Notably, these bills aimed to exclude independent spent fuel storage installations, like those at Prairie Island, from this category, thus changing how these facilities are regulated.

A pivotal element of these bills was the mandatory contribution of $500,000 annually for each dry cask of spent nuclear fuel to a renewable development account. This fund was designated to finance renewable energy projects across the state. Furthermore, the bills proposed granting additional dry cask storage capacity at Prairie Island. Despite passing from both the House and Senate, the bills from this session were indefinitely postponed.

However, in the same year, HF9 during a special session was passed, reinforcing these provisions and ensuring additional dry cask storage at Prairie Island.

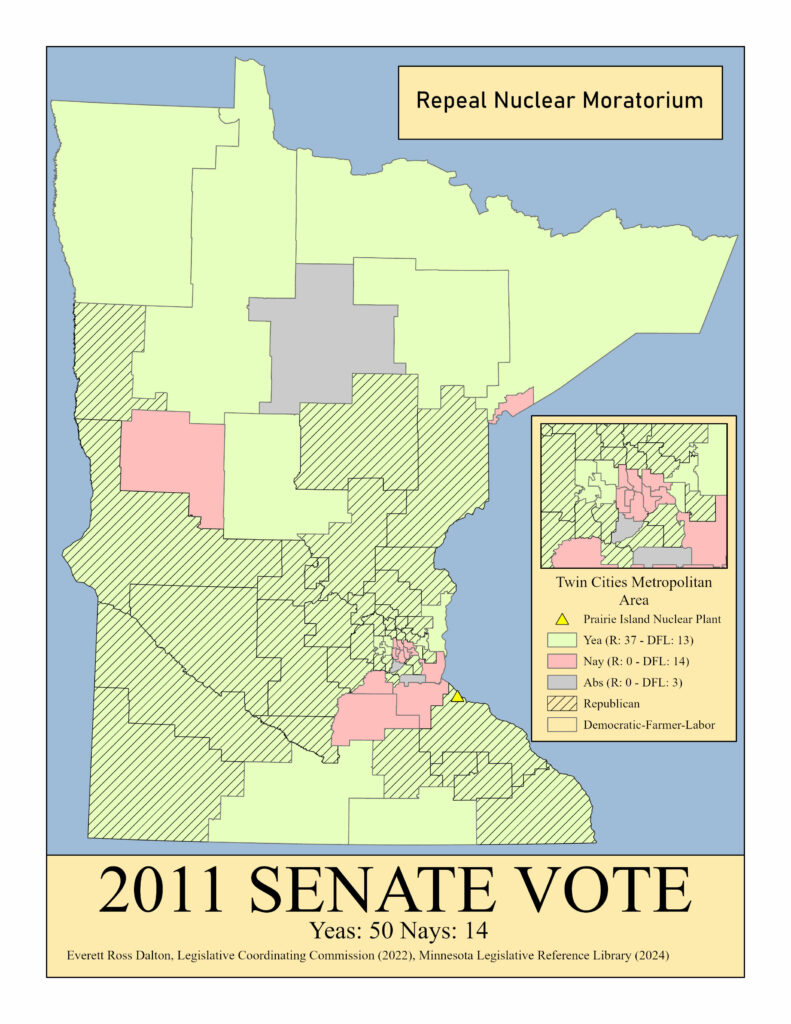

Continued Debate and the 2011 Proposals

Fast forward to 2011, and the debate over expanding nuclear capacity re-emerged with vigor. Proposals like SF4 and HF9 sought to lift the existing moratorium on new nuclear plant construction by abolishing the certificate of need for constructing new nuclear-powered electric generating plants. Although these proposals saw some legislative success (passing in the Senate 50-14 and in the House 81-50), they ultimately did not become law with the ongoing tensions about expanding nuclear power amidst evolving energy priorities.

The 2020 Vision: Renewable Integration

The narrative took a turn in 2020 with the introduction of the Prairie Island Net Zero Project. This project was not just another legislative item; it was a vision for the future, aiming to develop a net-zero emissions energy system for the Prairie Island Indian Community. This initiative underscored a shift towards integrating renewable energy solutions within nuclear communities, emphasizing sustainability and community support. The project was supported by a robust legislative mandate, passing in the House 84-49 and in the Senate 59-8.

Senator Andrew Mathews, R-Princeton, credit MNRSRC

Based on reporting by local news agencies as well as legislative records on bill authors and votes, nuclear energy appears to be a topic that isn’t cleanly split along party lines. That being said, it does seem like the majority of opposition to recent bills over the past few years has come from DFL members in the Minnesota House and Senate. In a piece published by the Minnesota Post in September of 2023, Senators Andrew Mathews (R-27) and Nick Frentz (D-18) attempted to rally support for Mathews proposed amendment on carve-outs for 300-megawatt reactors, an amendment that was ultimately not passed. Frentz and Mathews believe that the only way forward on this debate will be through bi-partisan efforts, and they themselves are trying to mirror just that. But as Frentz points out, “I said, ‘If you’re willing to store the nuclear waste in your district, Mathews, we can move this right along,’” Frentz said. “[Mathews] was not willing; to which I would say, ‘Everybody wants to go to heaven, nobody wants to die.’”

Sen. Nick Frentz, DFL-North Mankato, credit Elizabeth Dunbar and MPR News

As the MinnPost article addresses, much of the push back against bills pertaining to nuclear energy has come from the DFL in Minnesota. In the article, Senator John Marty, “The state’s longest-serving member of the Senate…represents that party line and was there when the moratorium was put into place”, gives his take on nuclear energy. According to Senator Marty, much of the opposition or hesitation within the DFL does not come from an outright rejection of nuclear, but rather, many members argue that “If we’re going to do it, fund it the way we fund coal plants and solar plants and other projects. They build them. They take the risk. And we pay for the power we buy,” Marty said. “But the proponents of repealing the moratorium never wanted that.”

Sen. John Marty, DFL-Roseville, credit Elizabeth Dunbar and MPR News

In tracking these various proposals and bills, a common theme in the process of attempting to modernize or restructure Minnesota’s nuclear energy program and infrastructure are the burdens of bureaucracy. Rather than hardline stances or rejections, many proposed bills simply come against the wall of session time limits and are expired before proper debate. Sometimes, language and clauses on nuclear energy are simply lost within bulky energy bills aiming to cover every topic and issue on energy policy in Minnesota.

In a year where Republicans made a deal with America and swept the country’s highest legislature, the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party maintained domination of both rural and urban house seats in the State of Minnesota. But unlike their Independent-Republican counterparts, they remained very divided on nuclear’s role in Minnesota

Sneaking it in a wider bill, both chambers of the Minnesota Legislature passed a bill that placed a moratorium on new nuclear power plants licensing; there would be no new plants in Minnesota.

Nearly two decades later, rebranded Republicans once again regained state legislatures all around the country during the Tea Party movement. Both chambers in the Minnesota legislature would be controlled by them.

The senate introduced the “Energy, Utilities and Telecommunications” act. This legislation allowed renewed nuclear licensing. It passed the Senate. Upon being introduced into the house several amendments were agreed to. These include new safety regulations, requiring local referenda for plants’ establishment, a barring of state investment for nuclear, amongst other changes. This high bar made permitting new plants highly difficult. The bill as amended passed the house, but was quickly rejected via voice vote upon return to the Senate.

The Senate convened a committee to reconcile the two chambers’ differing vision. Before this work could complete, the legislative session expired.

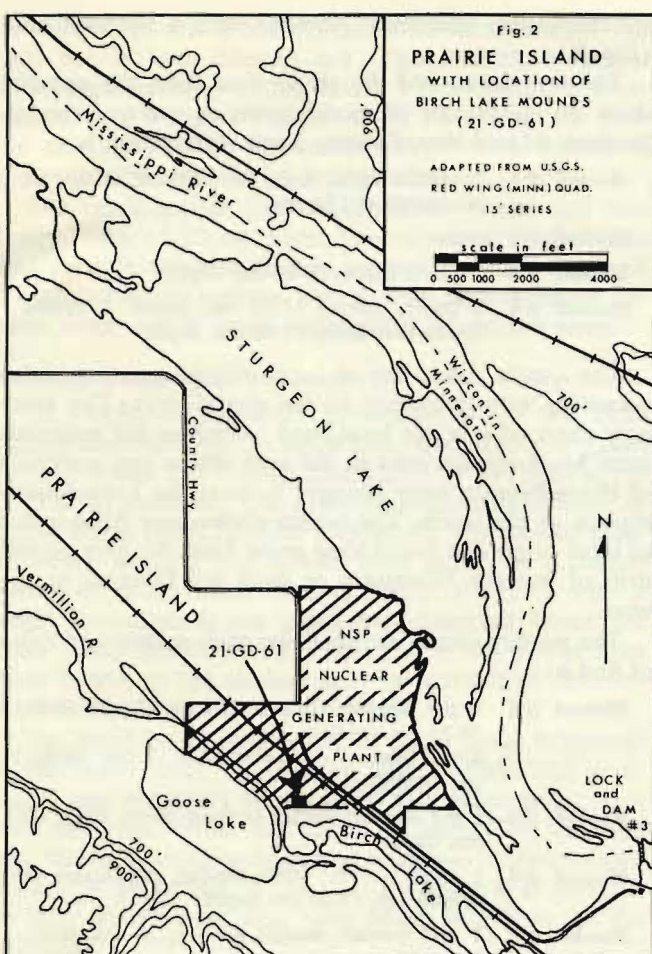

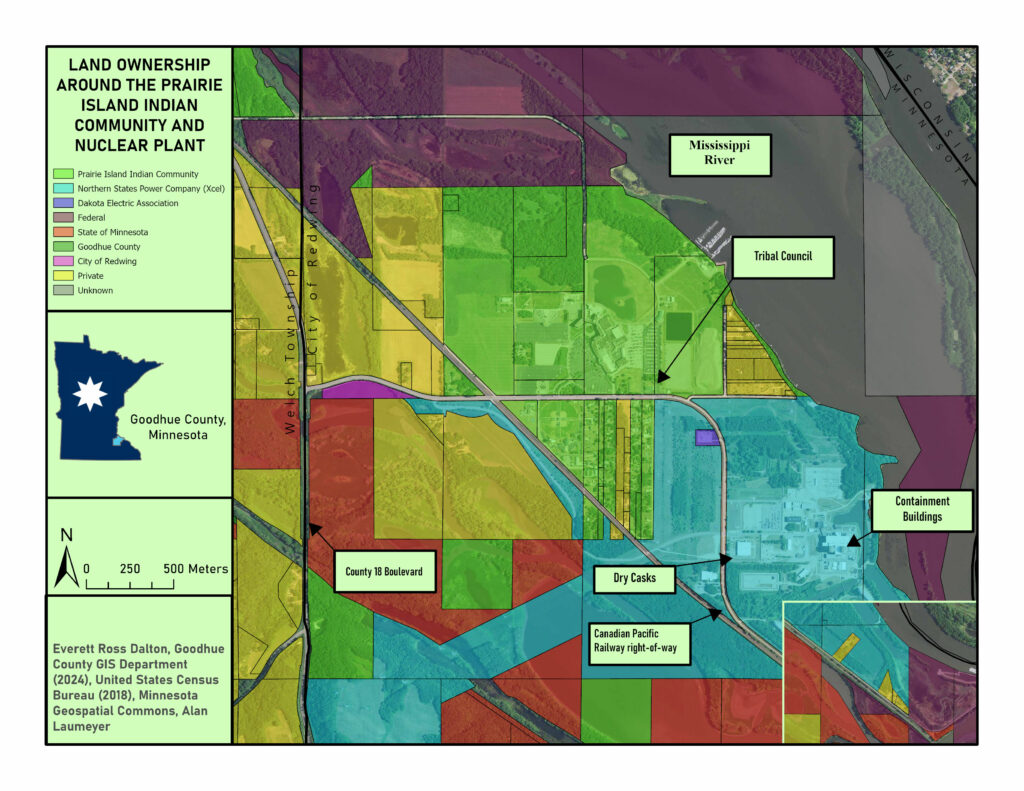

The Prairie Island Nuclear Plant is one of two contemporary plants in Minnesota. However, the location is highly contentious, standing a few hundred meters away from the Prairie Island Indian Community.

Xcel Energy subsidiary company, Northern States Power, is the primary land owner. Much of the parcels to the PIIC’s south are owned by the company. Here is where the nuclear power generation occurs and waste is stored, which notably, is in a flood plain. The company also owns plots across the bog through which their power lines run. To the south of Prairie Island (in the inset map in the bottom-right), one may notice how private properties are surrounded by company land.

The Indian Community’s land is surrounded by mostly unused municipal, county, state, and federal land. They share additional boarders with private entities and are a few hundred feet away from Wisconsin. Their limited land’s close contact to a nuclear plant and waste storage is a great source of anxiety for the community. The Canadian Pacific Railroad has a track running through the only exits on and off the Prairie Island.